Figure 19. The illustration of the MAVIS (above) is from Japanese Aircraft of the Pacific War by Rene J. Francillon (page 301).

A physical description of my part of the island is necessary to appreciate the next story. My foxhole was just inside an area covered by coconut and other trees. To the west was a small, white, sandy beach completely exposed and devoid of any vegetation. Directly behind the beach rose the hill, which was bare and almost cliff-like in this location. In the center of the little beach was a wooden box, perhaps two feet high and six feet long. We were told not to do anything to change the appearance of the island so the Japanese would not know if we were still there or not. In accordance with those instructions we dug a latrine under the box, cut a hole in the box top, and we now had a reasonably comfortable toilet. Although this location did not provide any privacy, it did offer a wonderful view of Sealark Channel and Florida Island.

One night a very good friend of mine, Jim McCrory, from Lemoore, California, needed to use the toilet. I happened to be on guard duty at the time. Jim called out softly and identified himself, as no one moved from his foxhole after dark without the sentry on duty in the squad knowing it first. I acknowledged him and Jim moved out. It was pitch black with no moon or other lights visible. Jim found the box and was utilizing its purpose when suddenly a bright light came on. A Japanese destroyer had silently moved in about a hundred yards offshore and then switched on its searchlight which happened to be centered on Jim sitting on the box. The ship was so close the beam of light was still quite small in circumference; it just covered Jim like a spotlight on a stage illuminates a performer. Jim froze, imagining all of those five-inch guns pointed at him, enough firepower to blow a warship out of the water! I was likewise frozen with fear as I knew a salvo fired at Jim would eliminate me too. The light held unwaveringly for what seemed like an eternity (it must have been a full minute) before swinging on down the beach. Although I could not hear anything, I could imagine both the unbelief and laughter aboard the ship. As soon as the light moved, Jim did too! Jim and I have remained very good friends over the years and keep in frequent contact via e-mail. We can now laugh over this incident.

The following day we were told to prepare to make Gavutu a second Corregidor, which was not very pleasant news as Corregidor had just fallen to the Japanese and all military personnel had been either killed or captured. Being abandoned and without supplies, we knew we would not have much chance of a different outcome. It may be of interest to some that never once did I hear a Marine discuss the possibility of surrender. We knew all too well the fate of prisoners held by the Japanese and no one planned to be one.

The night following the visit by the destroyer it returned again, continuing to use its searchlight but not firing any shots. On the third night it was back again, apparently just keeping an eye on things. The next day we were ordered to open fire with everything from thirty-caliber machine guns on up if it showed again. I didn't really appreciate this reasoning, as up to now no one had fired a shot and no one had been injured. The biggest gun we had on the island was a captured three-inch cannon mounted on the hill. The crew of that gun estimated they could get off three rounds before being knocked out. Other than that, we had a couple of 75 MM howitzers, a couple of 37 MM anti-tank guns, two or three .50-caliber machine guns, and our .30-caliber machine guns. None of these were any match for a destroyer that could just lie offshore and blow our whole island out of the water. Fortunately, the destroyer never returned.

We had one man in our platoon who had a fascination with high explosives. He was always carrying artillery shells and such items back to his foxhole, where he would proceed to dismantle them in order to see how they worked. As he had never had any training in this very dangerous pastime, we seriously questioned his IQ and made certain he had a foxhole by himself and some distance away from the rest of us.

In the early part of the war, American torpedoes were notorious for failing to explode due to defective fuses. This high failure rate was contributing greatly to severe losses among our submarines. As Gavutu had been a Japanese submarine base, a number of Japanese torpedoes were stacked near the causeway leading to Tanambogo. As opposed to American, Japanese torpedoes were famous for their reliability. Our curious private had spotted them, of course, and at his first opportunity he had taken one completely apart and studied it.

Two munitions personnel on Tulagi heard about our torpedoes so they came over to acquire a couple of them so they could be sent back to the States for study. These experts carefully stood at a distance contemplating how they were going to render these highly explosive items inert for shipping, especially as little was known about their assembly. Someone informed them of our man, so they came seeking him. He happily agreed to show them how things were done. Several of us accompanied these three people back to the torpedoes as we were now suddenly very proud of our resident expert. Upon arrival at the scene, we of little faith remained at a considerable distance and watched. Our man confidently sat astraddle the torpedo, bent over and removed the detonator. The real experts watched, but remained almost as far away as we were. They were so impressed, however, that they arranged to have him transferred to their unit. I never saw him again, and it is possible he ended his career with a real bang.

Shortly before our five and one-half weeks on Gavutu were over, a World War I four-stack destroyer arrived. This was the first American ship we had seen since the big sea battle. Our government figured this ship was expendable and we were told the crew had all volunteered. The ship had supplies for us as well as for our two battalions still stationed on Tulagi. A destroyer does not have much space to store supplies, and sharing among so many men meant that we would not receive much and starvation would continue, but at least we appreciated the thought. As the destroyer left across the channel, we were told it was sunk by Japanese aircraft.

We received orders to go to Guadalcanal to reinforce the First Division. The fighting there had started out slow but had become very ferocious as Japan was successfully reinforcing its troops. We had an old YP boat at Tulagi that would transport us. The YP was a converted fishing trawler with a wooden hull and slow speed, but it was all we had as our Navy still had not returned. On September 15, we left Gavutu, which was starting to feel like home, and departed for the 'Canal.'

Forty-six years later Joyce and I returned to Gavutu and Tanambogo. The islands that were so important and that cost at least 546 lives were completely deserted, with not a soul living on either. Gaomi Island had a native Melanesian family living there. The islands have completely recovered and were cloaked with jungle growth. I walked right to my foxhole site and pointed it out to Joyce. Both islands are beautiful and peaceful. One would never guess the horror that occurred there. Joyce could not believe how small the islands were.

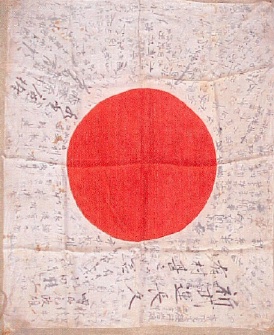

Figure 20. The Japanese battle flag taken by the author on Gavutu on August 8th, 1942.

Figure 21. Steve Goodhew (on right) holds one side of the flag. Steve attempted to build a resort on the island, but the venture was unsuccessful. I had returned the flag for permanent display on Gavutu. John Innes, a Solomon Islands historian from Guadalcanal, stands on the far right. The other two men are veterans visting the island. The photo was taken at the Gavutu end of the causeway that connects Tanambogo and Gavutu (also pictured in Figure 11). Gaomi and Florida islands can be seen in the background.

Figure 22. John Innes holds the flag on top of a small hill on Gavutu. This hill is the same one mentioned in the text that was accidentally bombed by an American aircraft. The other man is an American veteran visiting the island.